The haunting spectre of greenflation

The war in Ukraine is accelerating the energy transition and there is talk of a «double urgency», i.e. climate protection and energy security. Is there now a threat of greenflation?

Text: Dr Gerhard Wagner

Criticism of renewable energies has been silent these days. The war and climate crisis show that moving away from (Russian) fossil fuels both protects the climate and increases energy security. Nevertheless, the question is how expensive it will be for the economy and society if our economic system is to be able to make do with almost no fossil fuels by 2050 for climate protection and energy security. Arguments are made that hardly seem compatible:

- On the one hand, greenflation – that is rising energy prices due to new environmental technologies – is expected, which will effectively make the population poorer. The core argument is the high CO2 price required for climate protection. Former Chief Economist of the World Bank, Joseph Stiglitz, emphasises that cheap fossil fuels need to lose their cost advantage. If CO2 emissions are to be halved by 2030 to meet the 1.5°C climate protection target, this implies a CO2 price of USD 50 to 100 per tonne of CO2. Consumers will have to pay for this to make the energy transition possible. This will inevitably lead to greenflation.

- On the other hand, some climate protection advocates also anticipate greendeflation. For instance, they underpin their forecast by referring to significantly lower prices for solar modules. In 2008, the prices for a solar module were around USD 4 per watt. Today it is around USD 0.20 to 0.30 per watt.

With respect to solar energy, the term greenflation is undoubtedly wrong. The same applies to the price development of wind energy or batteries for electromobility.

What is inflationary and what is deflationary?

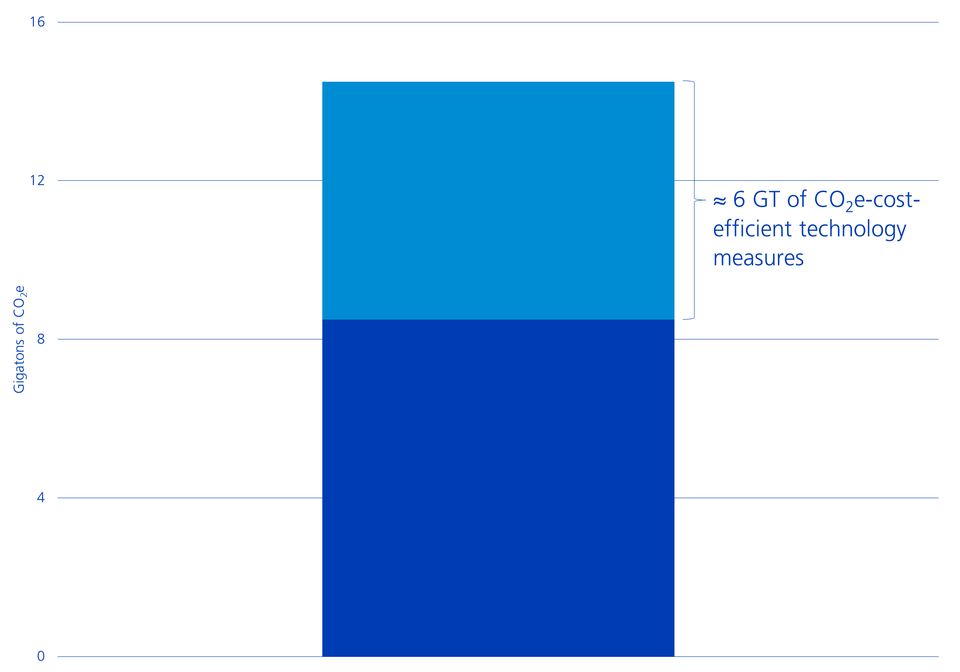

The International Energy Agency (IEA) is now trying to objectify the discussion regarding greenflation using detailed analyses to show which climate protection measures or technologies have an inflationary effect and which have a deflationary effect on energy prices. The IEA explains that, in addition to the CO2 reductions already planned as a result of the UN Climate Change Conference in Glasgow (COP26), a further 14 gigatonnes (GT) of CO2 must be saved by 2030 – an enormous feat without question.

Ambition gap in 2030

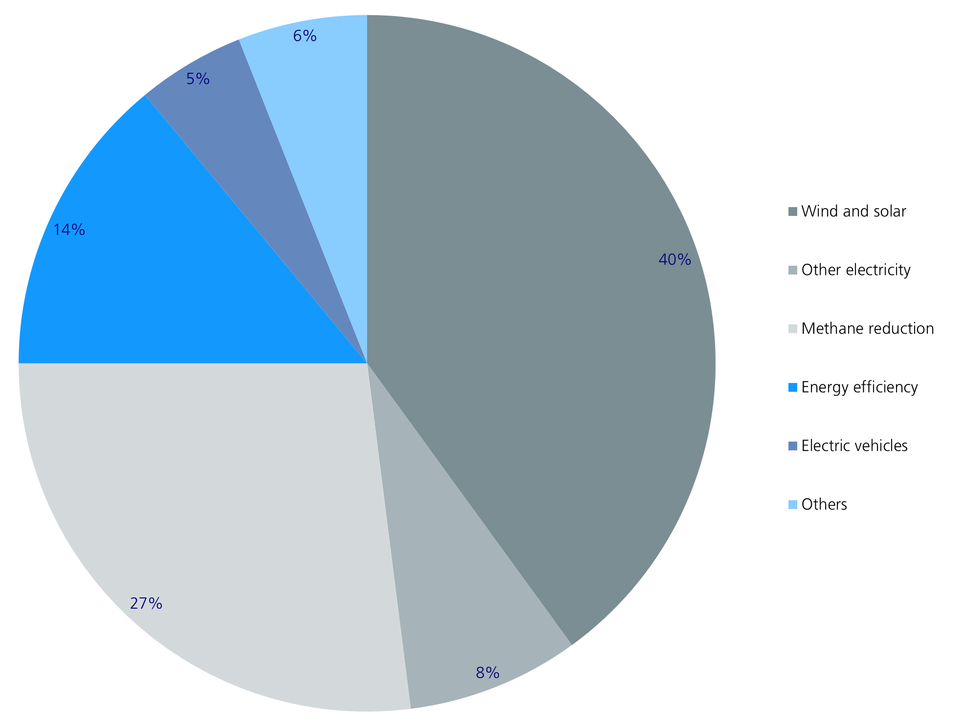

Nonetheless, around 40% or 5.6 GT could be saved with technologies that already appear cost-efficient or deflationary. These include electricity generation from wind and the sun, electromobility and numerous energy efficiency technologies.

Breakdown of CO2e-cost-efficient technology measures

The remaining 8 GT of CO2 that need to be reduced would still be covered by relatively expensive technologies. In this context, the term greenflation is accurate in that it makes energy more expensive for consumers. These include green hydrogen, CO2 storage or the removal of CO2 from the air. However, as mass production increases, costs should also fall here.

Higher energy costs are not inevitable

The IEA reaches the conclusion that if the global target of achieving a balance between the amount of CO2 emissions produced and the amount of CO2 emissions extracted from the atmosphere (net zero emissions) by 2050 is consistently pursued, thereby likely limiting global warming to 1.5°C, the average energy costs of the average household will not increase by 2030 compared to the period 2016 to 2020.

Nonetheless, in this scenario, households will have to shoulder large initial investments (e.g. home energy renovations) for which they will need state support. According to the IEA, the energy transition by 2030 is therefore not a cost problem for households, but a challenge in terms of of the available liquid funds for the necessary climate-friendly investments.

Provided that the IEA is right with its modelling, then it makes economic sense to tackle the energy transition consistently. The spectre of greenflation would not be a real problem. It would also be pleasing to see declining dependence on fossil fuels from Russia and other countries and this should lead to less volatility in energy costs. Last but not least, however, it is also important to note that dependency on other raw materials, such as copper, lithium and nickel, is increasing as a result of the energy transition.