Negative yields – at risk of extinction

For once, we are not dealing with the tragic extinction of species within the natural environment, but the welcome news that negative interest rates could once again soon become a curious but extinct phenomenon in economic history.

Text: Jan Strässle

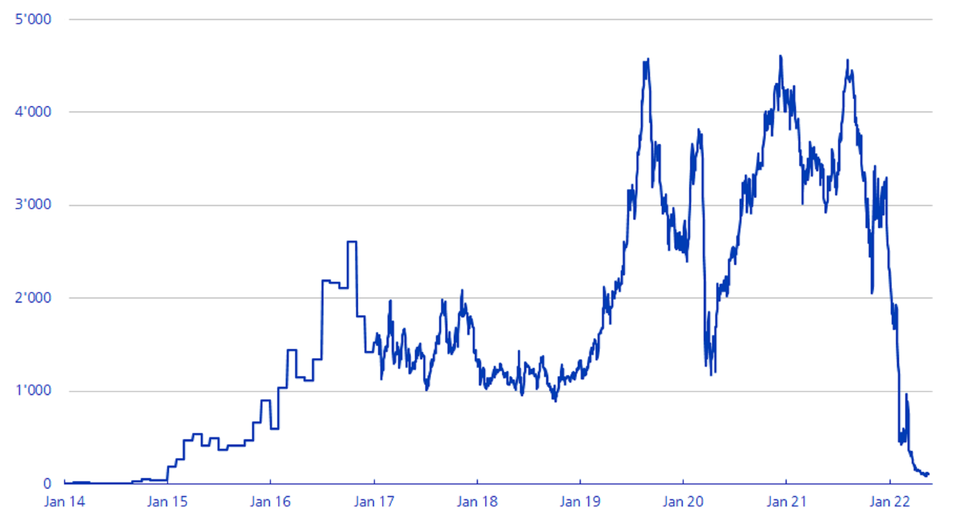

This is illustrated by the number of negative yielding bonds in the broad Bloomberg Global Aggregate benchmark index. This index does not contain any bonds with sub-year maturities, which is common for bond indices. The number of bonds with a negative yield to maturity has fallen since August 2021 from just under 4,600 to around 100.

Number of bonds with negative yields

The reason is the high inflation rates, which are forcing central banks to hike interest rates, sometimes quite drastically. For a long time, the opposite phenomenon was viewed a threat: deflationary tendencies were combated by various central banks through low interest rates and a desired currency devaluation. For a long time the parallel sharp increase in the debt of private and public borrowers did not seem to pose any danger. The power of the Phillips curve (rising inflation and wages with falling unemployment) seemed to have broken and even seduced some well-known economists into falling for some quite absurd ideas such as Modern Monetary Theory (MMT). However, inflation seems to be returning as a global phenomenon. Base effects as a result of the coronavirus pandemic have caused inflation to rise worldwide. Russia’s war of attack in Ukraine is once again raising the risk of inflation to a higher level. Are we witnessing a definite turnaround in yields, which is causing bonds with negative yields to die out?

Japan – an anachronism?

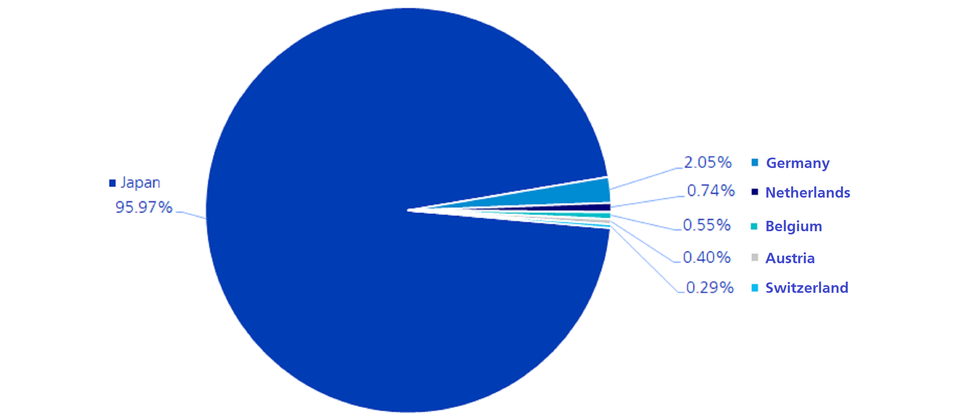

Further insights can be gained by looking at the remaining bonds with negative yields. The market capitalisation of bonds with negative yields is still well above USD 2 trillion. About 95% of these are partly accounted for by huge Japanese government bonds – the largest bond has a market value of more than USD 73 billion. The six remaining negative-yielding bonds in Swiss francs, on the other hand, are small and make up just 0.16% of the index.

Where are the yields still negative?

Shares of government bonds with negative yields

There are a number of reasons for this distribution. Just a few months ago, an interest rate hike by the European Central Bank (ECB) this year seemed an impossibility. But with inflation across the EU rising to 7.5% in April, an interest rate hike by the ECB is expected as early as this summer. In parallel with the ECB, the Swiss National Bank could also abandon its policy of negative interest rates.

The situation in Japan is different: Although inflation is rising sharply there too, expectations remain very low at almost 1.3% over 5 years. The Bank of Japan (BOJ) currently regards inflation as a transitory phenomenon, not a global one, and will not deviate from its policy of yield curve control. The artificially low Japanese yields are seriously punishing the currency, which has already lost ground against the USD (12% this year). This trend will further exacerbate inflationary pressures in Japan, which is why negative yields could ultimately also die out there.

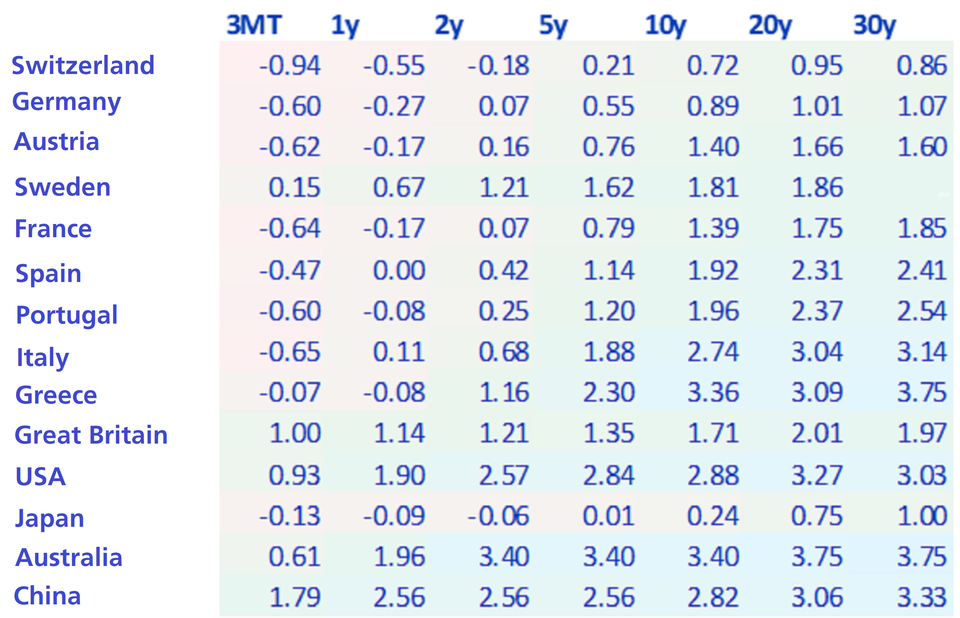

The interest rate hikes that have already taken place and those that are expected have already had a strong impact on global yield curves. Even though yields have still been markedly negative in many countries during this year, many longer-dated government bonds are now priced at very attractive levels again:

Yields mostly in the green again

Outlook – 35 years of rising yields?

Is this the turnaround in yields – or not? Various market observers report that the long-term downward trend in US yields has broken from a technical perspective. This development would be astonishing if the downward trajectory which the yield on the 10-year US Treasury interest rate has been on had existed since the 80s.

US Treasury Yield (10y)

Will there now be a 35-year climb in yields? No. And there are several reasons for this. The long downward trend was influenced by global megatrends. Globalisation, digitalisation and demographic trends (bigger labour force) have continued to weigh on inflation. But this configuration of factors will not be repeated.

The chances of negative yields dying out though are not low. Their benefits have been critically questioned time and again, which is why many central banks never let yields sink below zero. However, the negative effects such as the incorrect allocation of capital (zombie firms), market distortions (asset bubbles) and socio-economic problems (e.g. very low yields for pension funds) will continue to haunt us for some time to come. As we believe inflation is a global and persistent phenomenon at the moment, we are not expecting a fall back to negative yields, including in the event of an economic slowdown or even a recession. But we could also be mistaken on this point: It is important not to underestimate central banks’ desire in this day and age to resolve fiscal problems through monetary policy.

We are not alone in the expectation that inflation will soon exceed desired and tolerable levels in Japan as well. The BOJ must increasingly defend its yield curve controls against market forces, which cannot work in the long term. We are therefore confident negative yields will die out in Japan too – and will therefore no longer exist worldwide.

Positioning

We had anticipated this development in our active bond vehicles and had relatively heavily underweighted duration risks. However, since inflation now seems to have peaked in the USA, we have again built up somewhat longer-dated bonds there. The yield matrix (see above) shows that yield can be used to generate good income again. We remain cautious on bonds in EUR and CHF, where yields are likely to rise a little further. We are also circumspect about duration in Japan for the reasons mentioned. Since central banks can no longer intervene to any great degree in view of the risk of inflation, we are very much underweight in the European periphery (Italy, Spain and Portugal[1]). We are a little overweight in Australian bonds and Chinese duration. The Chinese 10-year yield has been listed below its US counterpart for the first time since 2010. As China does not currently have a promising plan to solve its major problems such as coronavirus and the real estate crisis, we believe that these yield spreads will continue to widen.

Whether negative interest rates are dying out – or not – there are lots of investors still in the bond market, such as central banks, who are not pursuing monetary interests. That’s why our motto “Keep active” remains as relevant as ever.

[1] Greece is not one our benchmarks due to its low credit rating. But the above assessment also applies to this country, which is why we are currently not holding any Greek government bonds.